Greece #51 (1876)

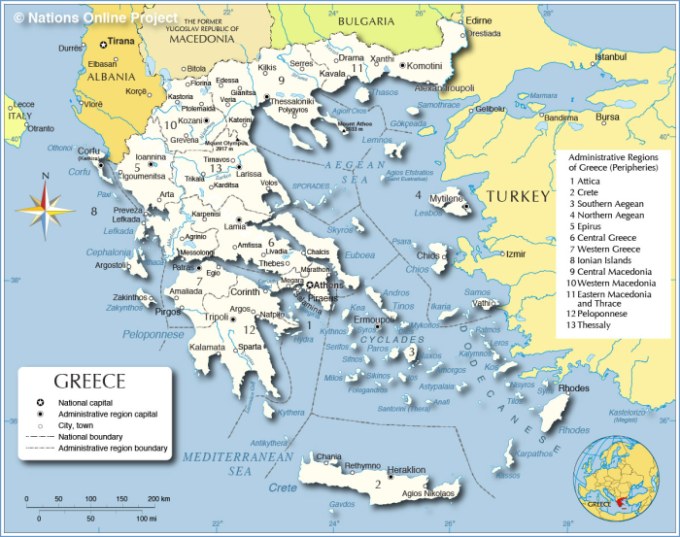

Greece (Elláda — Ελλάδα), officially the Hellenic Republic (Ellīnikī́ Dīmokratía — Ελληνική Δημοκρατία), historically also known as Hellas (Ἑλλάς), is a country in southeastern Europe, strategically located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Situated on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to the northeast. Greece consists of nine geographic regions: Macedonia, Central Greece, the Peloponnese, Thessaly, Epirus, the Aegean Islands (including the Dodecanese and Cyclades), Thrace, Crete, and the Ionian Islands. The Aegean Sea lies to the east of the mainland, the Ionian Sea to the west, the Cretan Sea and the Mediterranean Sea to the south. Greece has the longest coastline on the Mediterranean Basin and the 11th longest coastline in the world at 8,498 miles (13,676 kilometers) in length, featuring a vast number of islands, of which 227 are inhabited. Eighty percent of Greece is mountainous, with Mount Olympus being the highest peak at 9,573 feet (2,918 meters). Greece’s population is approximately 10.955 million as of 2015. Athens is the nation’s capital and largest city, followed by Thessaloniki.

Greece is considered the cradle of Western civilization, being the birthplace of democracy, Western philosophy, the Olympic Games, Western literature, historiography, political science, major scientific and mathematical principles, and Western drama. From the eighth century BC, the Greeks were organized into various independent city-states, known as polis, which spanned the entire Mediterranean region and the Black Sea. Philip of Macedon united most of the Greek mainland in the fourth century BC, with his son Alexander the Great rapidly conquering much of the ancient world, spreading Greek culture and science from the eastern Mediterranean to the Indus River. Greece was annexed by Rome in the second century BC, becoming an integral part of the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine Empire, wherein the Greek language and culture were dominant. The establishment of the Greek Orthodox Church in the first century AD shaped modern Greek identity and transmitted Greek traditions to the wider Orthodox World.Falling under Ottoman dominion in the mid-fifteenth century, the modern nation state of Greece emerged in 1830 following a war of independence. Greece’s rich historical legacy is reflected by its 18 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, among the most in Europe and the world.

Greece is a democratic and developed country with an advanced high-income economy, a high quality of life, and a very high standard of living. A founding member of the United Nations, Greece was the tenth member to join the European Communities (precursor to the European Union) and has been part of the Eurozone since 2001. It is also a member of numerous other international institutions, including the Council of Europe, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF). Greece’s unique cultural heritage, large tourism industry, prominent shipping sector and geostrategic importance classify it as a middle power. It is the largest economy in the Balkans, where it is an important regional investor.

The names for the nation of Greece and the Greek people differ from the names used in other languages, locations and cultures. Although the Greeks call the country Hellas or Ellada (Ἑλλάς or Ελλάδα) and its official name is the Hellenic Republic, in English it is referred to as Greece, which comes from the Latin term Graecia as used by the Romans, which literally means ‘the land of the Greeks’, and derives from the Greek name Γραικός.

The earliest evidence of the presence of human ancestors in the southern Balkans, dated to 270,000 BC, is to be found in the Petralona cave, in the Greek province of Macedonia. All three stages of the stone age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic) are represented in Greece, for example in the Franchthi Cave. Neolithic settlements in Greece, dating from the seventh millennium BC, are the oldest in Europe by several centuries, as Greece lies on the route via which farming spread from the Near East to Europe.

Greece is home to the first advanced civilizations in Europe and is considered the birthplace of Western civilization, beginning with the Cycladic civilization on the islands of the Aegean Sea at around 3200 BC, the Minoan civilization in Crete (2700–1500 BC), and then the Mycenaean civilization on the mainland (1900–1100 BC). These civilizations possessed writing, the Minoans writing in an undeciphered script known as Linear A, and the Mycenaeans in Linear B, an early form of Greek. The Mycenaeans gradually absorbed the Minoans, but collapsed violently around 1200 BC, during a time of regional upheaval known as the Bronze Age collapse. This ushered in a period known as the Greek Dark Ages, from which written records are absent.

The end of the Dark Ages is traditionally dated to 776 BC, the year of the first Olympic Games. The Iliad and the Odyssey, the foundational texts of Western literature, are believed to have been composed by Homer in the seventh or eighth centuries BC. With the end of the Dark Ages, there emerged various kingdoms and city-states across the Greek peninsula, which spread to the shores of the Black Sea, Southern Italy (“Magna Graecia“) and Asia Minor. These states and their colonies reached great levels of prosperity that resulted in an unprecedented cultural boom, that of classical Greece, expressed in architecture, drama, science, mathematics and philosophy. In 508 BC, Cleisthenes instituted the world’s first democratic system of government in Athens.

By 500 BC, the Persian Empire controlled the Greek city states in Asia Minor and Macedonia.[33] Attempts by some of the Greek city-states of Asia Minor to overthrow Persian rule failed, and Persia invaded the states of mainland Greece in 492 BC, but was forced to withdraw after a defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. A second invasion by the Persians followed in 480 BC. Following decisive Greek victories in 480 and 479 BC at Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale, the Persians were forced to withdraw for a second time, marking their eventual withdrawal from all of their European territories. Led by Athens and Sparta, the Greek victories in the Greco-Persian Wars are considered a pivotal moment in world history, as the 50 years of peace that followed are known as the Golden Age of Athens, the seminal period of ancient Greek development that laid many of the foundations of Western civilization.

Lack of political unity within Greece resulted in frequent conflict between Greek states. The most devastating intra-Greek war was the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), won by Sparta and marking the demise of the Athenian Empire as the leading power in ancient Greece. Both Athens and Sparta were later overshadowed by Thebes and eventually Macedon, with the latter uniting the Greek world in the League of Corinth (also known as the Hellenic League or Greek League) under the guidance of Phillip II, who was elected leader of the first unified Greek state in history.

Following the assassination of Phillip II, his son Alexander III (“The Great”) assumed the leadership of the League of Corinth and launched an invasion of the Persian Empire with the combined forces of all Greek states in 334 BC. Undefeated in battle, Alexander had conquered the Persian Empire in its entirety by 330 BC. By the time of his death in 323 BC, he had created one of the largest empires in history, stretching from Greece to India. His empire split into several kingdoms upon his death, the most famous of which were the Seleucid Empire, Ptolemaic Egypt, the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and the Indo-Greek Kingdom. Many Greeks migrated to Alexandria, Antioch, Seleucia, and the many other new Hellenistic cities in Asia and Africa. Although the political unity of Alexander’s empire could not be maintained, it resulted in the Hellenistic civilization and spread the Greek language and Greek culture in the territories conquered by Alexander. Greek science, technology, and mathematics are generally considered to have reached their peak during the Hellenistic period.

After a period of confusion following Alexander’s death, the Antigonid dynasty, descended from one of Alexander’s generals, established its control over Macedon and most of the Greek city-states by 276 BC. From about 200 BC, the Roman Republic became increasingly involved in Greek affairs and engaged in a series of wars with Macedon. Macedon’s defeat at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC signaled the end of Antigonid power in Greece. In 146 BC, Macedonia was annexed as a province by Rome, and the rest of Greece became a Roman protectorate.

The process was completed in 27 BC when the Roman Emperor Augustus annexed the rest of Greece and constituted it as the senatorial province of Achaea. Despite their military superiority, the Romans admired and became heavily influenced by the achievements of Greek culture, hence Horace’s famous statement: Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit (“Greece, although captured, took its wild conqueror captive”). The epics of Homer inspired the Aeneid of Virgil, and authors such as Seneca the younger wrote using Greek styles. Roman heroes such as Scipio Africanus, tended to study philosophy and regarded Greek culture and science as an example to be followed. Similarly, most Roman emperors maintained an admiration for things Greek in nature. The Roman Emperor Nero visited Greece in AD 66, and performed at the Ancient Olympic Games, despite the rules against non-Greek participation. Hadrian was also particularly fond of the Greeks; before he became emperor, he served as an eponymous archon of Athens.

Greek-speaking communities of the Hellenized East were instrumental in the spread of early Christianity in the second and third centuries, and Christianity’s early leaders and writers (notably St Paul) were mostly Greek-speaking, though generally not from Greece itself. The New Testament was written in Greek, and some of its sections (Corinthians, Thessalonians, Philippians, Revelation of St. John of Patmos) attest to the importance of churches in Greece in early Christianity. Nevertheless, much of Greece clung tenaciously to paganism, and ancient Greek religious practices were still in vogue in the late fourth century AD, when they were outlawed by the Roman emperor Theodosius I in 391–392. The last recorded Olympic games were held in 393, and many temples were destroyed or damaged in the century that followed. In Athens and rural areas, paganism is attested well into the sixth century AD and even later. The closure of the Neoplatonic Academy of Athens by the emperor Justinian in 529 is considered by many to mark the end of antiquity, although there is evidence that the Academy continued its activities for some time after that. Some remote areas such as the southeastern Peloponnese remained pagan until well into the tenth century AD.

The Roman Empire in the east, following the fall of the Empire in the west in the fifth century, is conventionally known as the Byzantine Empire (but was simply called “Roman Empire” in its own time) and lasted until 1453. With its capital in Constantinople, its language and literary culture was Greek and its religion was predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christian.

From the fourth century, the Empire’s Balkan territories, including Greece, suffered from the dislocation of the Barbarian Invasions. The raids and devastation of the Goths and Huns in the fourth and fifth centuries and the Slavic invasion of Greece in the seventh century resulted in a dramatic collapse in imperial authority in the Greek peninsula. Following the Slavic invasion, the imperial government retained formal control of only the islands and coastal areas, particularly the densely populated walled cities such as Athens, Corinth and Thessalonica, while some mountainous areas in the interior held out on their own and continued to recognize imperial authority. Outside of these areas, a limited amount of Slavic settlement is generally thought to have occurred, although on a much smaller scale than previously thought.

The Byzantine recovery of lost provinces began toward the end of the eighth century and most of the Greek peninsula came under imperial control again, in stages, during the ninth century. This process was facilitated by a large influx of Greeks from Sicily and Asia Minor to the Greek peninsula, while at the same time many Slavs were captured and re-settled in Asia Minor and those that remained were assimilated. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries the return of stability resulted in the Greek peninsula benefiting from strong economic growth — much stronger than that of the Anatolian territories of the Empire.

Following the Fourth Crusade and the fall of Constantinople to the “Latins” in 1204 mainland Greece was split between the Greek Despotate of Epirus (a Byzantine successor state) and French rule (known as the Frankokratia), while some islands came under Venetian rule. The re-establishment of the Byzantine imperial capital in Constantinople in 1261 was accompanied by the empire’s recovery of much of the Greek peninsula, although the Frankish Principality of Achaea in the Peloponnese and the rival Greek Despotate of Epirus in the north both remained important regional powers into the fourteenth century, while the islands remained largely under Genoese and Venetian control.

In the fourteenth century, much of the Greek peninsula was lost by the Byzantine Empire at first to the Serbs and then to the Ottomans. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, the Ottoman advance meant that Byzantine territory in Greece was limited mainly to its then-largest city, Thessaloniki, and the Peloponnese (Despotate of the Morea). After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, the Morea was the last remnant of the Byzantine Empire to hold out against the Ottomans. However, this, too, fell to the Ottomans in 1460, completing the Ottoman conquest of mainland Greece. With the Turkish conquest, many Byzantine Greek scholars, who up until then were largely responsible for preserving Classical Greek knowledge, fled to the West, taking with them a large body of literature and thereby significantly contributing to the Renaissance.

While most of mainland Greece and the Aegean islands was under Ottoman control by the end of the fifteenth century, Cyprus and Crete remained Venetian territory and did not fall to the Ottomans until 1571 and 1670 respectively. The only part of the Greek-speaking world that escaped long-term Ottoman rule was the Ionian Islands, which remained Venetian until their capture by the First French Republic in 1797, then passed to the United Kingdom in 1809 until their unification with Greece in 1864.

While some Greeks in the Ionian Islands and Constantinople lived in prosperity, and Greeks of Constantinople (Phanariotes) achieved positions of power within the Ottoman administration, much of the population of mainland Greece suffered the economic consequences of the Ottoman conquest. Heavy taxes were enforced, and in later years the Ottoman Empire enacted a policy of creation of hereditary estates, effectively turning the rural Greek populations into serfs.

The Greek Orthodox Church and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople were considered by the Ottoman governments as the ruling authorities of the entire Orthodox Christian population of the Ottoman Empire, whether ethnically Greek or not. Although the Ottoman state did not force non-Muslims to convert to Islam, Christians faced several types of discrimination intended to highlight their inferior status in the Ottoman Empire. Discrimination against Christians, particularly when combined with harsh treatment by local Ottoman authorities, led to conversions to Islam, if only superficially. In the nineteenth century, many “crypto-Christians” returned to their old religious allegiance.

The nature of Ottoman administration of Greece varied, though it was invariably arbitrary and often harsh. Some cities had governors appointed by the Sultan, while others (like Athens) were self-governed municipalities. Mountains regions in the interior and many islands remained effectively autonomous from the central Ottoman state for many centuries.

When military conflicts broke out between the Ottoman Empire and enemies, Greeks usually took arms against the empire, with few exceptions. Prior to the Greek Revolution of 1821, there had been a number of wars which saw Greeks fight against the Ottomans, such as the Greek participation in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, the Epirus peasants’ revolts of 1600–1601, the Morean War of 1684–1699, and the Russian-instigated Orlov Revolt in 1770, which aimed at breaking up the Ottoman Empire in favor of Russian interests. These uprisings were put down by the Ottomans with great bloodshed. On the other side, many Greeks were conscripted as Ottoman citizens to serve in the Ottoman army (and especially the Ottoman navy), while the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, responsible for the Orthodox, remained in general loyal to the empire.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are regarded as something of a “dark age” in Greek history, with the prospect of overthrowing Ottoman rule appearing remote with only the Ionian islands remaining free of Turkish domination. Corfu withstood three major sieges in 1537, 1571 and 1716 all of which resulted in the repulsion of the Ottomans. However, in the eighteenth century, there arose through shipping a wealthy and dispersed Greek merchant class. These merchants came to dominate trade within the Ottoman Empire, establishing communities throughout the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and Western Europe. Though the Ottoman conquest had cut Greece off from significant European intellectual movements such as the Reformation and the Enlightenment, these ideas together with the ideals of the French Revolution and romantic nationalism began to penetrate the Greek world via the mercantile diaspora. In the late eighteenth century, Rigas Feraios, the first revolutionary to envision an independent Greek state, published a series of documents relating to Greek independence, including but not limited to a national anthem and the first detailed map of Greece, in Vienna, and was murdered by Ottoman agents in 1798.

In the late eighteenth century, an increase in secular learning during the Modern Greek Enlightenment led to the revival among Greeks of the diaspora of the notion of a Greek nation tracing its existence to ancient Greece, distinct from the other Orthodox peoples, and having a right to political autonomy. One of the organizations formed in this intellectual milieu was the Filiki Eteria, a secret organization formed by merchants in Odessa in 1814. Appropriating a long-standing tradition of Orthodox messianic prophecy aspiring to the resurrection of the eastern Roman empire and creating the impression they had the backing of Tsarist Russia, they managed amidst a crisis of Ottoman trade, from 1815 onwards, to engage traditional strata of the Greek Orthodox world in their liberal nationalist cause. The Filiki Eteria planned to launch revolution in the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities and Constantinople. The first of these revolts began on March 6, 1821, in the Danubian Principalities under the leadership of Alexandros Ypsilantis, but it was soon put down by the Ottomans. The events in the north spurred the Greeks of the Peloponnese into action and on March 17, 1821, the Maniots declared war on the Ottomans.

By the end of the month, the Peloponnese was in open revolt against the Ottomans and by October 1821 the Greeks under Theodoros Kolokotronis had captured Tripolitsa. The Peloponnesian revolt was quickly followed by revolts in Crete, Macedonia and Central Greece, which would soon be suppressed. Meanwhile, the makeshift Greek navy was achieving success against the Ottoman navy in the Aegean Sea and prevented Ottoman reinforcements from arriving by sea. In 1822 and 1824 the Turks and Egyptians ravaged the islands, including Chios and Psara, committing wholesale massacres of the population. This had the effect of galvanizing public opinion in western Europe in favor of the Greek rebels.

Tensions soon developed among different Greek factions, leading to two consecutive civil wars. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Sultan negotiated with Mehmet Ali of Egypt, who agreed to send his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with an army to suppress the revolt in return for territorial gain. Ibrahim landed in the Peloponnese in February 1825 and had immediate success: by the end of 1825, most of the Peloponnese was under Egyptian control, and the city of Missolonghi — put under siege by the Turks since April 1825 — fell in April 1826. Although Ibrahim was defeated in Mani, he had succeeded in suppressing most of the revolt in the Peloponnese and Athens had been retaken.

After years of negotiation, three Great Powers, Russia, the United Kingdom, and France, decided to intervene in the conflict and each nation sent a navy to Greece. Following news that combined Ottoman–Egyptian fleets were going to attack the Greek island of Hydra, the allied fleet intercepted the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet at Navarino. After a week-long standoff, a battle began which resulted in the destruction of the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet. A French expeditionary force was dispatched to supervise the evacuation of the Egyptian army from the Peloponnese, while the Greeks proceeded to the captured part of Central Greece by 1828. As a result of years of negotiation, the nascent Greek state was finally recognized under the London Protocol in 1830.

Hellenic Post (Ελληνικά Ταχυδρομεία) was founded in 1828 along with the modern Greek state. In 1834, an agreement with French banker Feraldi ensured mail service to and from the islands, and in 1836 placed the first wagons for transporting mail between Athens and Piraeus. The first Greek-inscribed stamps were not issued by Greece proper, but by the nearby Ionian Islands. Under British rule from 1815 to 1864, this island group was known as the United States of the Ionian Islands. A set of three stamps was issued on May 15, 1859. Printed by Perkins, Bacon & Co. of London and inscribed ΙΟΝΙΚΟΝ ΚΡΑΤΟΣ (Ionian State), they depicted a profile of Queen Victoria. All were imperforate and bore no face value, this being indicated by their colors; orange (½ penny), blue (1 penny) and lake (2 pence). These stamps became invalid after the Ionian Islands were ceded to Greece on June 28, 1864.

In 1827, Ioannis Kapodistrias, from Corfu, was chosen by the Third National Assembly at Troezen as the first governor of the First Hellenic Republic. Kapodistrias established a series of state, economic and military institutions. Soon tensions appeared between him and local interests. Following his assassination in 1831 and the subsequent conference a year later, the Great Powers of Britain, France and Russia installed Bavarian Prince Otto von Wittelsbach as monarch. One of his first actions was to transfer the capital from Nafplio to Athens. In 1843 an uprising forced the king to grant a constitution and a representative assembly.

Due to his authoritarian rule, he was eventually dethroned in 1862 and a year later replaced by Prince Wilhelm (William) of Denmark, who took the name George I and brought with him the Ionian Islands as a coronation gift from Britain. In 1877 Charilaos Trikoupis, who is credited with significant improvement of the country’s infrastructure, curbed the power of the monarchy to interfere in the assembly by issuing the rule of vote of confidence to any potential prime minister.

The Greek god Hermes, messenger of the Gods in the Greek mythology, is the representation chosen, in 1860, by the Kingdom of Greece to illustrate its first postal stamps. which were issued in application of the law of 1853 on the stamping of the mail by the sender and by this of May 24, 1860, on the postal rates. A decree, dated the following June 10, announced the choice of Hermes, messenger of the Gods in the Greek mythology as the effigy of the stamps.

The stamps depict a profile of the Greek messenger god Hermes (Mercury) in a frame strongly resembling that used for contemporary stamps of France. The basic design was by the French engraver Albert Désiré Barre and the first batch was printed in Paris by Ernst Meyer. The nine values of the stamps of the “large Hermes head” were printed during more than twenty years from 1861 to 1882 from the same nine typographic plates. These stayed in circulation for 25 years from 1861 to 1886 before to being used again, overprinted, in 1900/1901.

The first set was issued on October 1, 1861. It consisted of seven denominations (1 lepton, 2, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 lepta). In November 1861 the printing plates were transferred to Athens and subsequent printings made there. The plates continued in use into the mid-1880s, resulting in a number of varieties due to plates becoming worn and then cleaned, as well as the printing of the stamps on several kinds of paper. Most types were also printed with control numbers on the back, and all were imperforate. Additional denominations (30 and 60 lepta) were introduced in 1876, to comply with the General Postal Union’s international letter rates (30 lepta for basic, 60 for registered letters).

The second stamp type of the Greek posts was also issued with the Hermes effigy. It is called the “small Hermes head” and was issued from 1886 to 1899. The stamps depict Hermes in profile, but with a smaller head and a rounder helmet. The design was by Henri Hendrickx (1817–1894) and it was engraved by Albert Doms, Atelier de Timbre, Belgium. The typographic plates counted 300 stamps, sub-divided in six panels of 50 stamps (5 × 10) mounted in two columns of three rows.

The stamps of the “small Hermes head” type were imperforate as well as perforated, with different perforations (13½, 11½ and 13¼). Like the “large Hermes head” stamps, the “small Hermes head” stamps were also overprinted in 1900 with two overprinted issues. The stamps were produced using the gravure method, using printing plates of 300 stamps in 6 groups of 50 stamps.

Greece’s first commemorative stamps were issued for the 1896 Summer Olympics, the first Olympic games in modern times. The series consisted of twelve values (1 lepton, 2, 5, 10, 20, 25, 40 and 60 lepta, 1 drachma and 2, 5 and 10 drachmae). There were eight different designs, by Professor I. Svoronos, which included famous sports-related images from ancient Greece, such as a chariot race and Myron’s Discobolus. The stamps were designed by Swiss artist A. Guilleron, the steel dies were created by the French engraver Louis-Eugène Mouchon and printing took place at the National Printing Office of France. The name E. MOUCHON appears at the bottom side of each stamp. The stamps were delivered in perforated sheets (13½ x 14). They were at first meant to be sold only during the Games, but their circulation period was extended; first to March 1897, then until they were sold out.

Corruption and Trikoupis’ increased spending to create necessary infrastructure like the Corinth Canal overtaxed the weak Greek economy, forcing the declaration of public insolvency in 1893 and to accept the imposition of an International Financial Control authority to pay off the country’s debtors. Another political issue in nineteenth-century Greece was uniquely Greek: the language question. The Greek people spoke a form of Greek called Demotic. Many of the educated elite saw this as a peasant dialect and were determined to restore the glories of Ancient Greek.

Government documents and newspapers were consequently published in Katharevousa (purified) Greek, a form which few ordinary Greeks could read. Liberals favored recognizing Demotic as the national language, but conservatives and the Orthodox Church resisted all such efforts, to the extent that, when the New Testament was translated into Demotic in 1901, riots erupted in Athens and the government fell (the Evangeliaka). This issue would continue to plague Greek politics until the 1970s.

All Greeks were united, however, in their determination to liberate the Greek-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire, regardless of the dialect they spoke. Especially in Crete, a prolonged revolt in 1866–1869 had raised nationalist fervor. When war broke out between Russia and the Ottomans in 1877, Greek popular sentiment rallied to Russia’s side, but Greece was too poor, and too concerned of British intervention, to officially enter the war. Nevertheless, in 1881, Thessaly and small parts of Epirus were ceded to Greece as part of the Treaty of Berlin, while frustrating Greek hopes of receiving Crete.

Greeks in Crete continued to stage regular revolts, and in 1897, the Greek government under Theodoros Deligiannis, bowing to popular pressure, declared war on the Ottomans. In the ensuing Greco-Turkish War of 1897, the badly trained and equipped Greek army was defeated by the Ottomans. Through the intervention of the Great Powers, however, Greece lost only a little territory along the border to Turkey, while Crete was established as an autonomous state under Prince George of Greece. With state coffers empty, fiscal policy came under International Financial Control. In the next decade, Greek efforts were focused on the Macedonian Struggle, a state-sponsored guerilla campaign against pro-Bulgarian rebel gangs in Ottoman-ruled Macedonia, which ended inconclusively with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908.

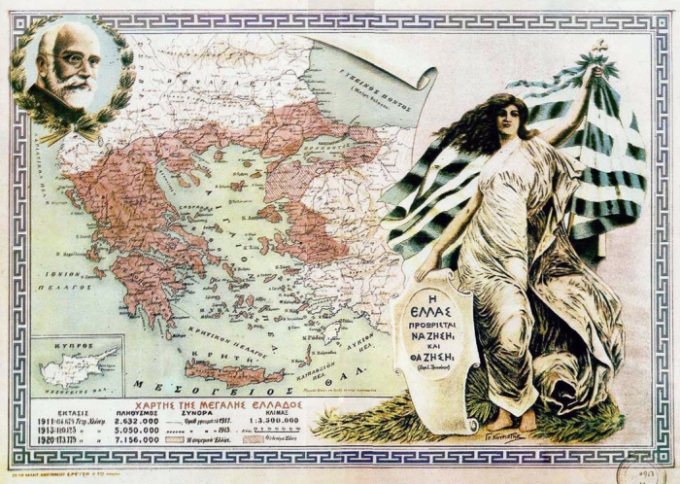

Amidst general dissatisfaction with the state of the nation, a group of military officers organized a coup in August 1909 and shortly thereafter called to power Cretan politician Eleftherios Venizelos. After winning two elections and becoming Prime Minister, Venizelos initiated wide-ranging fiscal, social, and constitutional reforms, reorganized the military, made Greece a member of the Balkan League, and led the country through the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913.

Greece’s borders were greatly expanded by the Balkan Wars as it occupied Macedonia including the city of Thessaloniki, parts of Epirus and Thrace and various Aegean islands, as well as formally annexing Crete. Until these so-called “New Territories” were formally incorporated into Greece, they were not permitted to use regular Greek stamps. In order to cover postal needs in these areas, Greece’s government ordered existing stamps to be overprinted with ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗ ΔΙΟIΚΗΣΙΣ (Hellenic Administration) until a planned 1912 issue became available. A special overprint, ΛΗΜΝΟΣ, was also ordered for use on the island of Lemnos, which was occupied in October 1912. These overprints, in three different colors (black, red and carmine), were applied to the 1911 “Engraved” definitives, the 20 lepta Flying Mercury stamp, the 1902 postage due stamps and some of the 1913 “Lithographic” definitives. This issue went through several printings, initially by Aspiotis Bros. and later by the Aquarone printing house of Thessaloniki. The overprints normally read from the bottom of the stamp to the top; due to misplacement of sheets in the printing press, some were released with the overprint reading from top to bottom.

A variation of this overprint, consisting of the letters “Ε.*Δ” in red, was employed on the island of Chios in 1913. This was applied locally to a quantity of 25 lepta stamps from the ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗ ΔΙΟIΚΗΣΙΣ issue which were mistakenly delivered without the overprint.

In the following years, the struggle between King Constantine I and charismatic Venizelos over the country’s foreign policy on the eve of World War I dominated the country’s political scene, and divided the country into two opposing groups. During parts of World War I, Greece had two governments; a royalist pro-German government in Athens and a Venizelist pro-Entente one in Thessaloniki. The two governments were united in 1917, when Greece officially entered the war on the side of the Entente.

In the aftermath of World War I, Greece attempted further expansion into Asia Minor, a region with a large native Greek population at the time, but was defeated in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, contributing to a massive flight of Asia Minor Greeks. These events overlapped, with both happening during the Greek genocide (1914–1922), a period during which, according to various sources, Ottoman and Turkish officials contributed to the death of several hundred thousand Asia Minor Greeks. The resultant Greek exodus from Asia Minor was made permanent, and expanded, in an official Population exchange between Greece and Turkey. The exchange was part of the terms of the Treaty of Lausanne which ended the war.

The following era was marked by instability, as over 1.5 million propertyless Greek refugees from Turkey had to be integrated into Greek society. Cappadocian Greeks, Pontian Greeks, and non-Greek followers of Greek Orthodoxy were all subject to the exchange as well. Some of the refugees could not speak the language, and were from what had been unfamiliar environments to mainland Greeks, such as in the case of the Cappadocians and non-Greeks. The refugees also made a dramatic post-war population boost, as the amount of refugees was more than a quarter of Greece’s prior population.

Following the catastrophic events in Asia Minor, the monarchy was abolished via a referendum in 1924 and the Second Hellenic Republic was declared.

Greece’s first airmail stamps, known as the “Patagonia set”, were released in mid-October 1926. They were intended for use on airmail letters from Greece to Italy and Turkey, and produced by the Italian firm Aero Espresso Italiana (AEI). The design, by A. Gavalas, depicted flying boats against various backgrounds. The set was printed in Milan, Italy, reputedly by the firm Bestetti & Tumminelli, and consisted of four values (2, 3, 5 and 10 drachmae). This issue remained in circulation until 1933, when it was replaced by the zeppelin and “Aeroespresso” issues, also produced by AEI.

The zeppelin issue, consisting of three values (30, 100 and 120 drachmae), was issued May 2, 1933, and remained on sale until May 27. It was released in connection with the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin’s May 29 flight to Rome and depicted a zeppelin flying over the Acropolis of Athens.

In 1935, a royalist general-turned-politician Georgios Kondylis took power after a coup d’état and abolished the republic, holding a rigged referendum, after which King George II returned to Greece and was restored to the throne.

An agreement between Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas and the head of state George II followed in 1936, which installed Metaxas as the head of a dictatorial regime known as the 4th of August Regime, inaugurating a period of authoritarian rule that would last, with short breaks, until 1974. Although a dictatorship, Greece remained on good terms with Britain and was not allied with the Axis.

On October 28, 1940, Fascist Italy demanded the surrender of Greece, but the Greek administration refused, and, in the following Greco-Italian War, Greece repelled Italian forces into Albania, giving the Allies their first victory over Axis forces on land. The Greek struggle and victory against the Italians received exuberant praise at the time. Most prominent is the quote attributed to Winston Churchill: “Hence we will not say that Greeks fight like heroes, but we will say that heroes fight like Greeks.” French general Charles de Gaulle was among those who praised the fierceness of the Greek resistance. In an official notice released to coincide with the Greek national celebration of the Day of Independence, De Gaulle expressed his admiration for the Greek resistance:

“In the name of the captured yet still alive French people, France wants to send her greetings to the Greek people who are fighting for their freedom. The 25th of March 1941 finds Greece in the peak of their heroic struggle and in the top of their glory. Since the Battle of Salamis, Greece had not achieved the greatness and the glory which today holds.”

The country would eventually fall to urgently dispatched German forces during the Battle of Greece, despite the fierce Greek resistance, particularly in the Battle of the Metaxas Line. Adolf Hitler himself recognized the bravery and the courage of the Greek army, stating in his address to the Reichstag on December 11, 1941, that: “Historical justice obliges me to state that of the enemies who took up positions against us, the Greek soldier particularly fought with the highest courage. He capitulated only when further resistance had become impossible and useless.”

The Nazis proceeded to administer Athens and Thessaloniki, while other regions of the country were given to Nazi Germany’s partners, Fascist Italy and Bulgaria. The occupation brought about terrible hardships for the Greek civilian population. Over 100,000 civilians died of starvation during the winter of 1941–1942, tens of thousands more died because of reprisals by Nazis and collaborators, the country’s economy was ruined, and the great majority of Greek Jews were deported and murdered in Nazi concentration camps. The Greek Resistance, one of the most effective resistance movements in Europe, fought vehemently against the Nazis and their collaborators. The German occupiers committed numerous atrocities, mass executions, and wholesale slaughter of civilians and destruction of towns and villages in reprisals. In the course of the concerted anti-guerilla campaign, hundreds of villages were systematically torched and almost 1,000,000 Greeks left homeless. In total, the Germans executed some 21,000 Greeks, the Bulgarians 40,000, and the Italians 9,000.

After liberation and the Allies’ win over Axis, Greece annexed the Dodecanese islands. Soon the country experienced a polarizing civil war between communist and anticommunist forces until 1949, which led to economic devastation and severe social tensions between rightists and largely communist leftists for the next thirty years.[88] The next twenty years were characterized by marginalization of the left in the political and social spheres and by rapid economic growth, propelled in part by the Marshall Plan.

Greece’s highest development visibility during the twentieth century, is also seen by its HDI component-numeracy, which increased rapidly during this period, respectively even though low levels of human capital level persisted even sometime after Ottoman rule ended.

King Constantine II’s dismissal of George Papandreou’s centrist government in July 1965 prompted a prolonged period of political turbulence which culminated in a coup d’état on April 21, 1967, by the Regime of the Colonels. The brutal suppression of the Athens Polytechnic uprising on November 17, 1973, is claimed to have sent shockwaves through the regime, and a counter-coup overthrew Georgios Papadopoulos to establish brigadier Dimitrios Ioannidis as leader. On July 20, 1974, as Turkey invaded the island of Cyprus, the regime collapsed.

The former prime minister Konstantinos Karamanlis was invited back from Paris where he had lived in self-exile since 1963, marking the beginning of the Metapolitefsi era. The first multiparty elections since 1964 were held on the first anniversary of the Polytechnic uprising. A democratic and republican constitution was promulgated on June 11, 1975, following a referendum which chose to not restore the monarchy.

Meanwhile, Andreas Papandreou, George Papandreou’s son, founded the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) in response to Karamanlis’s conservative New Democracy party, with the two political formations dominating in government over the next four decades. Greece rejoined NATO in 1980. Greece became the tenth member of the European Communities (subsequently subsumed by the European Union) on January 1, 1981, ushering in a period of sustained growth. Widespread investments in industrial enterprises and heavy infrastructure, as well as funds from the European Union and growing revenues from tourism, shipping, and a fast-growing service sector raised the country’s standard of living to unprecedented levels. Traditionally strained relations with neighboring Turkey improved when successive earthquakes hit both nations in 1999, leading to the lifting of the Greek veto against Turkey’s bid for EU membership.

The country adopted the euro in 2001 and successfully hosted the 2004 Summer Olympic Games in Athens. More recently, Greece has suffered greatly from the late-2000s recession and has been central to the related European sovereign debt crisis. Due to the adoption of the euro, when Greece experienced financial crisis, it could no longer devalue its currency to regain competitiveness. Youth unemployment was especially high during the 2000s. The Greek government-debt crisis, subsequent austerity policies, and resultant protests have agitated domestic politics and have regularly threatened European and global financial markets since the crisis began in 2010.

Scott #51 is denominated 30 lepta and printed in dark brown. It is classified by the Scott catalogue as “Athens Print, Coarse Impression, Yellowish Paper” and was released in 1876. In 1875, following Greece’s admittance to the Union Générale des Postes (U.G.P.), ancestor of the Union Postale Universelle (Universal Postal Union — U.P.U.), the Greek postal administration ordered the printing of two new values (30 and 60 lepta ). These were printed from the same die used in 1861 to build the typographic plates of the first seven values, Désiré-Albert Barre has created the plates for the 30 lepta (brown) and the 60 lepta (green) necessary for the international mail. Unlike the seven first typographic plates realized in 1861 with the “direct striking in the coining press” method, these two new plates were manufactured under the supervision of Désiré-Albert Barre with the “Galvanoplasty-type” method by the company of Charles-Dierrey, located at numbers 6 & 12 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in Paris. These two values were printed by J. Claye & Cie at 7 rue Saint Benoît, in Paris. After a first printing of the two values in Paris, all the following stamps were printed in Athens with the same typographic plates sent from Paris.