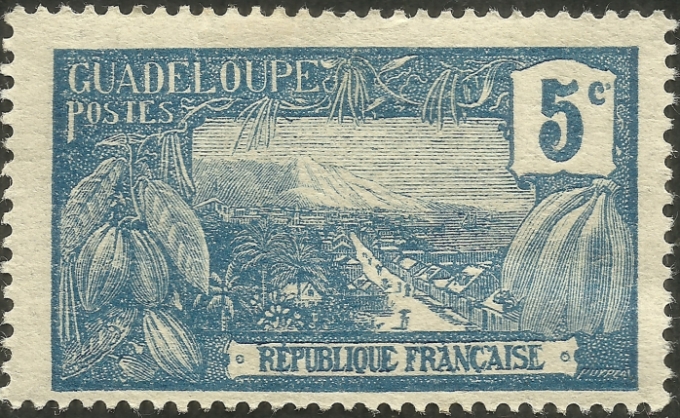

Guadeloupe #58 (1922)

Guadeloupe is an insular region of France located in the Leeward Islands, part of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. Administratively, it is an overseas region consisting of a single overseas department. It has a land area of 629 square miles (1,628 square kilometers) and an estimated population of 400,132 as of January 2015. Guadeloupe’s two main islands are Basse-Terre to the west and Grande-Terre to the east, which are separated by a narrow strait that is crossed with bridges. They are often referred to as a single island. The department also includes the Dependencies of Guadeloupe which include the smaller islands of Marie-Galante and La Désirade, and the Îles des Saintes. Guadeloupe, like the other overseas departments, is an integral part of France. It is thus part of the European Union and the Eurozone, and its currency is the euro. As an overseas department, Guadeloupe is not part of the Schengen Area. The prefecture (regional capital) of Guadeloupe is the city of Basse-Terre, which lies on the island of the same name. The official language is French, and virtually the entire population except recent arrivals from metropolitan France also speaks Antillean Creole (Créole Guadeloupéen).

The island was called Karukera (or “The Island of Beautiful Waters”) by the Arawak people, who settled on there in 300 AD/CE. During the eighth century, the Caribs came and killed the existing population of Amerindians on the island.

During his second trip to the Americas, in November 1493, Christopher Columbus became the first European to land on Guadeloupe, while seeking fresh water. He called it Santa María de Guadalupe de Extremadura, after the image of the Virgin Mary venerated at the Spanish monastery of Villuercas, in Guadalupe, Extremadura. The expedition set ashore just south of Capesterre, but left no settlers behind. Columbus is credited with discovering the pineapple on the island of Guadeloupe in 1493, although the fruit had long been grown in South America. He called it piña de Indias, which can be correctly translated as “pine cone of the Indies.”

During the seventeenth century, the Caribs fought against the Spanish settlers and repelled them.

After successful settlement on the island of St. Christophe (St. Kitts), the French Company of the American Islands delegated Charles Lienard (Liénard de L’Olive) and Jean Duplessis Ossonville, Lord of Ossonville to colonize one or any of the region’s islands, Guadeloupe, Martinique, or Dominica. Due to Martinique’s inhospitable nature, the duo resolved to settle in Guadeloupe in 1635, took possession of the island, and wiped out many of the Carib Amerindians. It was annexed to the kingdom of France in 1674.

Over the next century, the British seized the island several times. The economy benefited from the lucrative sugar trade, which commenced during the closing decades of the seventeenth century. Guadeloupe produced more sugar than all the British islands combined, worth about £6 million a year. The British captured Guadeloupe in 1759. The British government decided that Canada was strategically more important and kept Canada while returning Guadeloupe to France in the Treaty of Paris (1763) that ended the Seven Years War.

In 1790, following the outbreak of the French Revolution, the monarchists of Guadeloupe refused to obey the new laws of equal rights for the free people of color and attempted to declare independence. The ensuing conflict with the republicans, who were faithful to revolutionary France, caused a fire to break out in Pointe-à-Pitre that devastated a third of the town. The monarchists ultimately overcame the republicans and declared independence in 1791. The monarchists then refused to receive the new governor that Paris had appointed in 1792. In 1793, a slave rebellion broke out, which made the upper classes turn to the British and ask them to occupy the island.

In an effort to take advantage of the chaos ensuing from the French Revolution, Britain seized Guadeloupe in 1794, holding control from April 21 until December 1794, when republican governor Victor Hugues obliged the British general to surrender. Hugues succeeded in freeing the slaves, who then turned on the slave owners who controlled the sugar plantations.

In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte issued the Law of May 20, 1802. It restored slavery to all of the colonies captured by the British during the French Revolutionary Wars, but did not apply to certain French overseas possessions such as Guadeloupe, Guyane, and Saint-Domingue. Napoleon sent an expeditionary force to recapture the island from the rebellious slaves. Louis Delgrès and a group of revolutionary soldiers killed themselves on the slopes of the Matouba volcano when it became obvious that the invading troops would take control of the island. The occupation force killed approximately 10,000 Guadeloupeans.

On February 4, 1810, the British once again seized the island and continued to occupy it until 1816. By the Anglo-Swedish alliance of March 3, 1813, it was ceded to Sweden for a brief period of fifteen months. During this time the British administration continued in place and British governors continued to govern the island.

In the Treaty of Paris of 1814, Sweden ceded Guadeloupe once more to France. An ensuing settlement between Sweden and the British gave rise to the Guadeloupe Fund. The Treaty of Vienna in 1815 definitively acknowledged French control of Guadeloupe.

Slavery was finally abolished on the island (and in all French possessions) on May 28, 1848 at the initiative of Victor Schoelcher. Guadeloupe lost 12,000 of its 150,000 residents in the cholera epidemic of 1865–66.

In 1925, after the trial of Henry Sidambarom (Justice of the Peace and defender of the cause of Indian workers), Raymond Poincaré decided to grant French nationality and the right to vote to Indian citizens.

In 1946, the colony of Guadeloupe became an overseas department of France. Then in 1974, it became an administrative center. Its deputies sit in the French National Assembly in Paris.

In 2007, the island communes of Saint-Martin and Saint-Barthélemy were officially detached from Guadeloupe and became two separate French overseas collectivities with their own local administration. Their combined population was 35,930 and their combined land area was 28.6 square miles (74.2 km²) as of the 1999 census.

In January 2009, an umbrella group of approximately fifty labor union and other associations (known in the local Antillean Creole as the Liyannaj Kont Pwofitasyon (LKP), led by Élie Domota) called for a €200 ($260 USD) monthly pay increase for the island’s low income workers. The protesters have proposed that authorities “lower business taxes as a top up to company finances” to pay for the €200 pay raises. Employers and business leaders in Guadeloupe have said that they cannot afford the salary increase. The strike lasted 44 days, ending with an accord reached on March 5, 2009. Tourism suffered greatly during this time and affected the 2010 tourist season as well. The 2009 French Caribbean general strikes exposed deep ethnic, racial, and class tensions and disparities within Guadeloupe.

Postal handstamps are known from 1780 and datestamps from 1843, but there was no regular inland mail service until 1849. Stamps of France were used in Guadeloupe from 1851 and French Colonies general issues from 1859. These can be recognized by the postmarks, including a lozenge of dots with the letters GRE. Surcharges with the initials G.P.E. were released in 1884 and inscribed GUADELOUPE beginning in 1889. During World War II, the island sided with de Gaulle and used Free French stamps during 1940-1944. Guadeloupe became an overseas departement of France on March 19, 1946, and has used the stamps of France since 1947.

Scott #58 was issued in 1922, part of a long-running pictorial set of 29 values released between 1905 and 1927. The 5-centime deep blue tyopgraphed stamp, perforated 14×13½, pictures the habor at Basse-Terre, located in the south-western corner of the Basse-Terre portion of the island of Guadeloupe. It is the prefecture (capital city) of Guadeloupe and lies at the foot of the Soufrière volcano (seen on this stamp). Although it is the administrative capital, Basse-Terre is only the second largest city in Guadeloupe behind Pointe-à-Pitre. Together with its urban area it had 44,864 inhabitants in 2012 (11,534 of whom lived in the city of Basse-Terre proper).

Before Basse-Terre became a French town it was a village of American Indian horticulturists and potters. The village was on the site of the present Basse-Terre Cathedral where archaeological excavations found human remains and other evidence of occupation during the restoration of the cathedral. In 2005 on the lower part of a Native American garbage dump, excavations have uncovered a new dump containing large amounts of archaeological material: food waste, ceramics, stone tools and shell tools, ornaments, charcoal and a tomb.

In 1635, when it was part of Saint Kitts and Nevis, an expedition was seeking a place of lasting presence in Guadeloupe. The operation was entrusted to Charles Liénard de l’Olive and Jean du Plessis d’Ossonville together with 4 missionaries and 550 colonists. The landing took place on June 28, 1635, at Pointe Allègre, far from Basse-Terre. Famine pushed the party to the south near the present town of Vieux-Fort in early 1636. The relationship between Native Americans and colonists degraded quickly; Liénard then began a bloody war against the locals. In 1660, a treaty forced him to retreat to Dominica and Saint Vincent. The war forced him to build a fort, today Fort Olive at Vieux Fort.

In 1640, Aubert succeeded Liénard as the government of the island and he soon left the site to settle on the left bank of the Galion, which is the current Gourbeyre marina. In 1643, Charles Houël du Petit Pré replaced Aubert and, in 1649, he left the marina site for the right bank of the Galion and built a fort. Some religious built the first church, now the Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, shortly afterwards and the city was organized around the chapel and from the fort to the river of Herbs. This was the beginning of Basse-Terre.

Around 1680, on the right bank of the river of Herbs, the Capuchins build a chapel dedicated to Saint Francis of Assisi where the present Guadeloupe Cathedral is located and a second center of population grew around this place of worship. The River of Herbs separated the two distinct villages: Basse-Terre and Saint Francis. In reality, people flocked to the new town because of attacks by the English who burned the town of Basse-Terre in 1691 and again in 1703. Following these raids the people thought that the fort was attracting the invaders and consequently moved to Saint Francis. A stone bridge was built in 1739 replacing a ford and a wooden bridge across the River of Herbs.

In 1976, 73,600 inhabitants of the town were evacuated (from August 15 to November 18) due to the high activity of the Soufrière volcano. Some evacuees never returned and moved to Jarry. For 20 years, the town center was depopulated in favor of peri-urban areas or neighboring towns such Baillif, Saint-Claude, and Gourbeyre despite attempts at renewal.